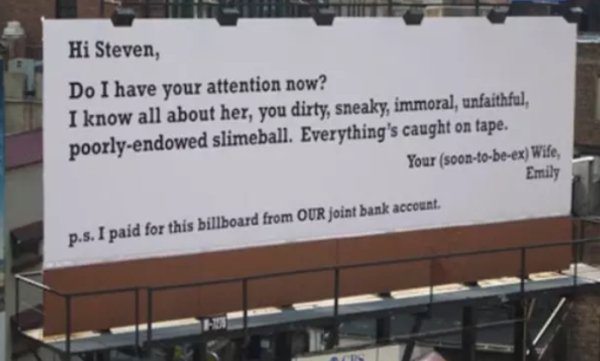

“Adulterous Slut Lives Here.”

While shaming a soon-to-be former spouse on social media—or, in this case, on plywood—may provide a measure of short term emotional satisfaction, doing so may actually hinder your chances of achieving your goals in the Family Court.

It is important to know that the Family Court is not perfect. It is presided over by judges who are human, who carry their own stresses and virtues and predispositions onto the bench every day. And, while we have court rules and state statutes that ideally govern how we operate in that system, and while we certainly have case law that aids in the interpretation thereof, those Family Court judges wield a lot of power from their spot on high. Further, if a judge’s decision is unsatisfactory to a litigant, the appeals process—both in the short term for temporary decisions and in the long term for permanent ones—can be cumbersome, unpredictable, costly, and anything but quick.

As a result, we try to keep matters and issues out of the courtroom where possible. It’s not that dramatic hearings aren’t helpful or fun (for us attorneys, at least), but that the results therefrom can be all over the map. While we generally know what issues to put in front of a judge and advise clients as to same, there have been occasions when a judge’s decision appeared to ignore fact and law, and left us scratching our collective heads – sometimes with a result better than projected, other times worse.

In South Carolina, we have four fault grounds for divorce: (1) Physical Cruelty; (2) Adultery; (3) Habitual Drunkenness and Drug Abuse; and (4) Desertion. We also have options when it comes to a no-fault divorce, and obtaining a final and permanent settlement arrangement that resembles a legal separation. Notwithstanding those specific grounds, and especially for those nonmarried litigants, cases may begin in any number of ways—physical or emotional abuse, drug and alcohol abuse, parental alienation, financial strain, denial of visitation, child abuse, or maybe even just two people who don’t get along anymore—but cases only resolve in one of two ways: (1) agreement, or (2) trial.

Trials are expensive. Trials are unpredictable. And, by the time a particular case progresses all the way to a trial, numerous attempts to settle the case via agreement will have come and gone. Mediation will have been held. If it’s a custodial matter, a Guardian ad Litem will have investigated the situation on behalf of the child or children, and will be prepared to apprise the court of his or her findings. Many, many thousands of dollars will be spent on attorneys, Guardians ad Litem, and perhaps even psychological evaluators, real estate appraisers, forensic accountants, and other experts. These are funds that instead could be earmarked for children’s college education, vacations, or other things that will have a lasting, positive affect in a child’s life. As a result, we look to agreement as the alternative to trial.

Resolving a matter by agreement requires detail, focus, and a little bit of finesse. No matter how perfect the litigant or talented the attorney, no party will obtain everything they want in the Family Court, but that doesn’t mean that the most important goals cannot be achieved. That said, how do you convince an estranged spouse to agree to something they inherently do not wish to do? Two methods come to mind: leverage, and lack of alternative.

With regard to any settlement agreement, the measure of whether an agreement is good or bad as to a specific issue is whether that agreement is better than or equal to what a Family Court judge might do at trial. This, of course, is a subjective assessment, made possible only by the experience of a good attorney and a knowledge of facts and law and how each might be perceived by our stable of judges. If an estranged spouse does not wish to go to trial on a particular issue or issues, then that spouse is more likely to agree to things to which they might not otherwise be amenable.

That, my friends, brings us to plywood, Facebook, and that aforementioned short-term emotional satisfaction.

It’s not that an estranged spouse might take exception to being publicly shamed in some sort of way and for that reason refuse to engage in good faith settlement negotiations, though that is a possibility. The more likely way that your previous pursuit of short-term emotional satisfaction affects your case in the long term is how that estranged spouse—or, more likely, his or her attorney—assesses the risk of taking a particular issue to trial with the knowledge that a Family Court judge will have to consider whatever public shaming took place.

When it comes to issues like child custody and visitation, alimony and child support, and even the distribution of assets and debts, the court looks to various factors – all of which can be found in the pages of our firm’s website. Each set of factors for each of those issues include factors that may be influenced by behavior and action driven by emotional response.

In child custody actions, for example, the court considers 17 factors in accordance with S.C. Code § 63-15-240(B). One factor considered by the court includes “the actions of each parent to encourage the continuing parent child relationship between the child and the other parent, as is appropriate.” In other words, the court wants to see that one parent is ready, willing, and able to foster and facilitate a healthy and bonded relationship with the other parent. If that parent has littered social media—and perhaps the interstate—with example after example of how he or she is likely to allow emotion to get the better of him or her, it is not that lengthy of a logical leap to consider that the same parent is unlikely to facilitate a healthy and bonded relationship between the child and the other parent that they clearly and unambiguously abhor.

When it comes to alimony and spousal support, pursuant to S.C. Code Ann. §20-3-130(C) the court considers 13 different factors, one of which is “other factors the court considers relevant.” Similarly, S.C. Code Ann. §20-3-620 sets forth 15 different factors considered by the court in the distribution of marital assets and debts, one of which is “such other relevant factors as the trial court shall expressly enumerate in its order.” Is it likely that a Family Court judge will consider the actions of one party or another when distributing property or setting alimony? That answer varies from judge to judge and situation to situation, but most attorneys would rather present the judge with a victim of circumstance than a vindictive instigator any day of the week.

Actions and behaviors can even affect the possibility of the court issuing an order requiring that the other party reimburse attorney’s fees and costs. S.C. Code Ann. §20-3-130(H) authorizes the Family Court to order payment of litigation expenses to either party in a divorce action, and certainly such payments may be ordered in cases between nonmarried parties as well. When the court assesses whether a party is entitled to attorney’s fees and, if so, to how much, Family Court judges again turn to a number of factors. One of those factors, derived from Glasscock v. Glasscock, 304 S.C. 158, 161, 403 S.E.2d 313, 315 (1991) and other similar cases, is “[t]he nature, extent, and difficulty of the case.” If the emotionally-driven behavior and actions of one party causes the other party to incur additional fees, this is absolutely something that may be considered by the court in the assessment thereof.

Our jurisprudence is littered with case law that reinforce this. In Anderson v. Tolbert, 322 S.C. 543, 549-50, 473 S.E.2d 456, 459 (Ct.App. 1996), the Court of Appeals noted that an uncooperative party whose actions did much to prolong and hamper a final resolution of the issues should not be rewarded for that conduct. In Spreeuw v. Barker, 385 S.C. 45, 72-73, 682 S.E.2d 843 (Ct. App. 2009), the Court of Appeals held that if a party’s lack of cooperation and misconduct in the litigation process increased the amount of fees incurred by the other party, then the court could use this as the basis for an additional fee award. And in Donahue v. Donahue, 299 S.C. 353, 365, 384 S.E.2d 741, 748 (1989), the South Carolina Supreme Court similarly held that a husband’s lack of cooperation serves as an additional basis for the award of attorney’s fees.

During the process of assessing the good and bad of any proposed settlement agreement, a party will weigh that which the agreement provides against how much that party wants to go to trial instead. If that party spent days, weeks, and months disparaging, harassing, and shaming the other party for all to see, how a judge would perceive those actions will certainly weigh into whether or not an agreement is a better alternative than trial.

We do this every day, and we have the pleasure of watching people as they grow stronger throughout what is inevitably a difficult process. Even if we do not have firsthand knowledge from our own lives as to what you are going through—and sometimes we do—we still have the experience of assisting hundreds of people through these situations and this process.

So, before taking pen to paper, before telling Facebook what’s on your mind, and before buying plywood and spray paint at the Home Depot, come in and talk to us. While it may not be as immediately satisfying to bite your tongue and refrain from telling the world where that adulterous slut lives, at the end of the day doing so could actually translate into more time with your children or thousands of dollars in your pocket.